Abstract

Exploring depictions of divinity in Renaissance art opens up rabbit holes of research – one being conspiracies and the other being comparative mythology, which tends to be received as cantankerous, as revealed by a review of Joseph Campbell’s work by Dennis Patrick Slattery (2004). In escape of these exhausted examples of study into conspiracy and mythology, this research focuses on the epitome of divinity in Renaissance art – bringing to light where necessary the presence and relevance of conspiracies and myths in a Judeo-Christian based era for the sake of understanding how to recreate the effect of the time.

Introduction

This essay explores the definition of divinity in Renaissance art, on the basis of visuals and context. Recent reproductions of Renaissance themes in chosen works are used as evidence of the appeal to a modern audience. The research presented enriches the final body of work, iDivine, with explanations of what methodology will execute the uncovered criteria from the research. The criteria for the project success are listed below.

I. Symbols and symmetry

II. Storytelling, spirituality and the supernatural

III. Celestial art

IV. Luminance and colour

These areas of success criteria will be used to evaluate the final practical work.

I. Symbols and Symmetry

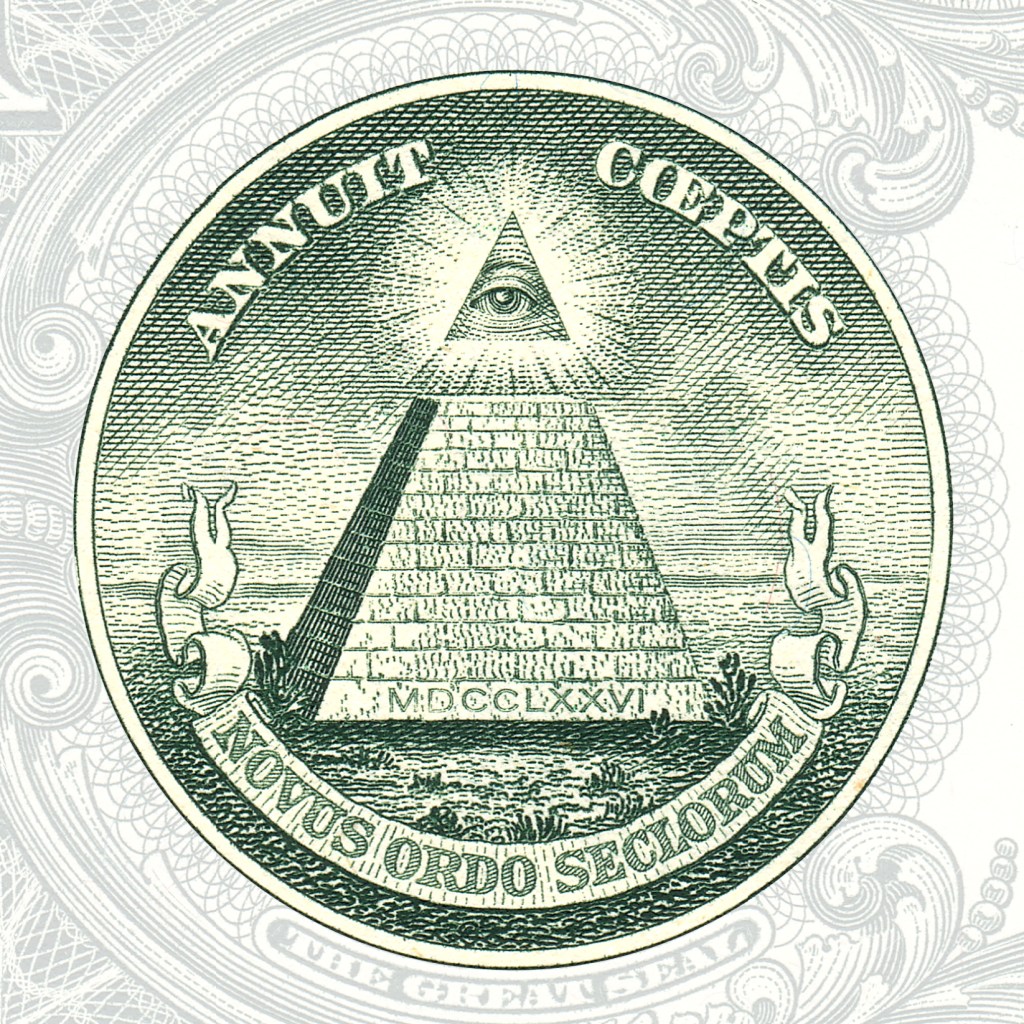

Renaissance art easily conjures mental imagery of both religious and erotic figures. Either heavily robed and demure, or athletic and provocatively nude. However, deeper symbolism can be missed by the most avid museum goer or gallery fiend. The first study in this journey through the divine Renaissance is Raphael Urbino, and the symbols in The Transfiguration (1516). Originally commissioned by wealthy patron Giulio de Medici who later became Pope Clement VII, the painting gives insight into the manipulation behind powerful religious arts. Raphael, who worked on The Transfiguration until his death, was coerced into making the painting for the Medici’s ambitions of separating religion from the myths of the Greek middle-ages and paganism. Raphael’s use of chiaroscuro liberally contrasts with the enlightenment of Christ. The hidden triangles in The Transfiguration represent the divine providence which eventually became a staple symbol of the Illuminati.

The Proportion and Design of Raphael’s ‘Transfiguration’, Lecture Diagram 10 circa 1810 Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775-1851 Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/D17134

J. W. Turner illustrated an example of The Transfiguration, highlighting that the triangles and symmetry gives a nod to the rise in science at the time – as well as Pythagoras who we know is favoured by the Raphael as he appears in another of his works, The School of Athens (1509). By using this symbolism, Raphael suggests that a beauty that exists in one’s mind is greater than the body. He allows us to focus on the intellectual aspect of our dual nature: our mind over our bodies, since our bodies are fleeting terrestrial forms and choosing to incorporate the eternal truth of mathematics.

The intention of the artist to satisfy his commissioners whilst embracing symbols that satisfy himself and those of maths or philosophy, is a trend that arguably fuelled a rise in anti-religious societies. Being devout Christians did not stop artists like Raphael from combining their faith with contemporary themes or symbols. This trend has led to the conspiracies about the affiliation between church, state and societies such as the Illuminati and the Freemasons. Specifically, in the widely popular series of books by Dan Brown such as Angels & Demons (2000), which generated appeal in numerous blockbuster films – pulling on the conspiracy theories behind many Renaissance art and texts.

Dan Brown’s dark and twisted interpretation of the divine presence in the Renaissance is eye-opening to the deeper meanings of the works and corruption during that time. The stories follow Robert Langdon, a symbologist, through treasure hunts to uncover divine mysteries in the thrilling series of stories. Arguably, the reason the books and film adaptations by Ron Howard are so popular lies in the natural inquisitiveness about the Renaissance; the time that illustrated our most sacred texts. The art evokes reverence but the symbology provokes blasphemy. With this in mind, hidden symbols and symmetry are the first criteria for recreating Renaissance divinity for a modern audience.

II. Storytelling, Spirituality and the Supernatural

Much of mankind’s societies and the stories we tell have been generated from our understanding of our own existence – our history and our morality. The Bible, being the most influential books of all, is responsible for a lot of the visuals and structures of the stories we have today. The common thread in this discreetly religious tapestry of existence are these things; the supernatural, the fall from grace and the restoration of hope (rebirth).

The divine aesthetic of hope is an inherent part of modern storytelling, which we identify through the story arc and climax. After an unsolvable problem when all seems lost, the main character rises in the face of extreme adversity. This story structure is outlined in The Alchemy of Animation (2008) where Don Hahn reveals the making of an animated film in the modern age, however this divine aesthetic of hope is traced back to Renaissance art that illuminates bible scriptures.

First in the visual storytelling of divinity in Renaissance art, we see the supernatural – a superhuman concept that presents itself as the place in which to fall from. In modern storytelling this is referred to as the story set-up. Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1512) illustrates the Bible verse Genesis 2:7. The scene presents supernatural elements by showing God who is floating, enveloped in a billowing red cloak. A languid Adam extends his hand to God to receive the divine, shown through the golden ratio that builds tension around the point of contact. The visual tension in the gap between the fingers indicates that the divinity God bestows on Adam is intellect – since God seemingly appears in the outline of a brain and Adam is already physically formed. The supernatural event is the initial part of the story as well as contributing to beliefs in the origin our existence.

The Fall of Man otherwise known as The Fall and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1512) by Michelangelo demonstrates the test that creates sin and turmoil. This inciting incident builds tension and rises to the climax. The Temptation prefigures the crucifixion. Michelangelo acknowledged death through the tree and life through the cross and therefore composed the tree to foreshadow the cross in which Jesus was crucified on.

Hope is restored by the death and rebirth of Jesus Christ. Giotto shows The Crucifixion (1320) which uses earthy tones to signify the lamentation of death. The Pietà (1498) a statue by Michelangelo, also known as The Lamentation is a reminder of the falling action before the resolution in modern storytelling. When the main character dies in a story we expect a grand return, a rebirth. This monomyth has become part of the human psyche and appears in stories throughout time, revealing a universal hero. Renaissance art anchors the human potential visually by illuminating the ultimate boon of freedom after hardship in the world’s greatest story of rebirth. The Transfiguration is an example of this restoration of hope.

Many superhero stories use core concepts that already occupy real estate in the audience’s mind from divine scenes in Renaissance art. For example, Superman (1938) wears a red cape and descends from the sky, much like Michelangelo’s depiction of God in ‘The Creation of Adam’. In the final shot of Batman v Superman (2016) we explicitly see that a resurrection of a deceased Superman is imminent. The original creators of the superhero revealed they moulded him around their Judeo-Christian tales and upbringing. This reveals to us a second criteria for making divinity in Renaissance art appealing to a modern audience by using a supernatural story structure that immortalises Christ by stories that reiterate patterns of his hardship and rebirth.

III. Celestial Art.

Towards the end of the Renaissance, divinity was depicted as more light and airy and less earthy and apocalyptic. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1696, created paintings founded on the High Renaissance that were ceiling frescoes and altarpieces. Allegory of Merit Accompanied by Nobility and Virtue exemplifies the light in colour and airy in feel aesthetic that has influenced much of our impression of divinity.

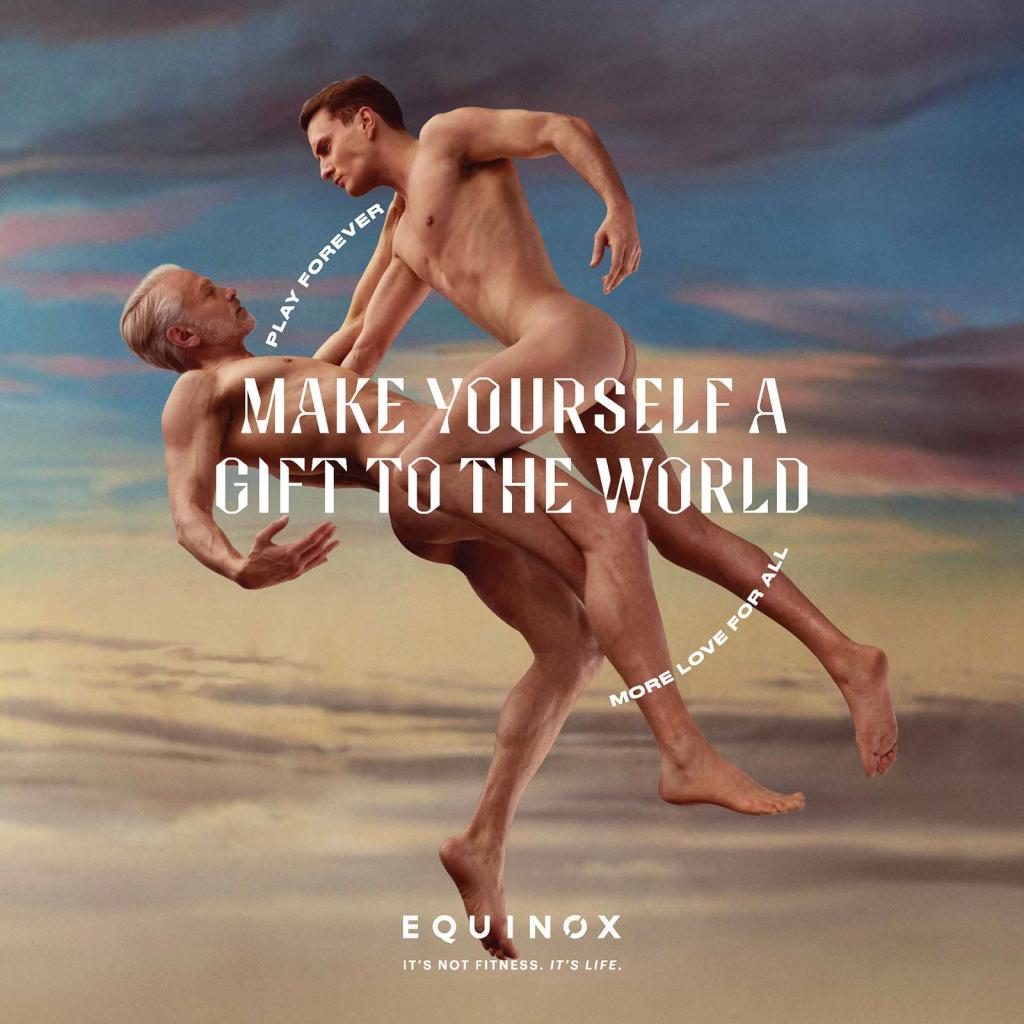

The use of blue skies and clouds follow from Tiepolo’s painting to Equinox, a modern sports brand that released a series of works for their latest campaign that have latched onto this theme. The homoerotic revival of the traditional Renaissance style adds the inherent controversial and provocative elements from the era.

Furthermore, there is a striking similarity to elements in the advert and The Creation of Adam which also uses a grey-haired God and brown-haired Adam replicated in the 2020 poster, as well as the sky background and the pronounced hand form. The tagline “Make Yourself a Gift to the World” plays on the gift that was life from God in his creation of mankind and the world, specifically using the verb to make which is a synonym to create. The overtones are romantic and offer us a welcome escape to reinvent ourselves for the sake of a better world.

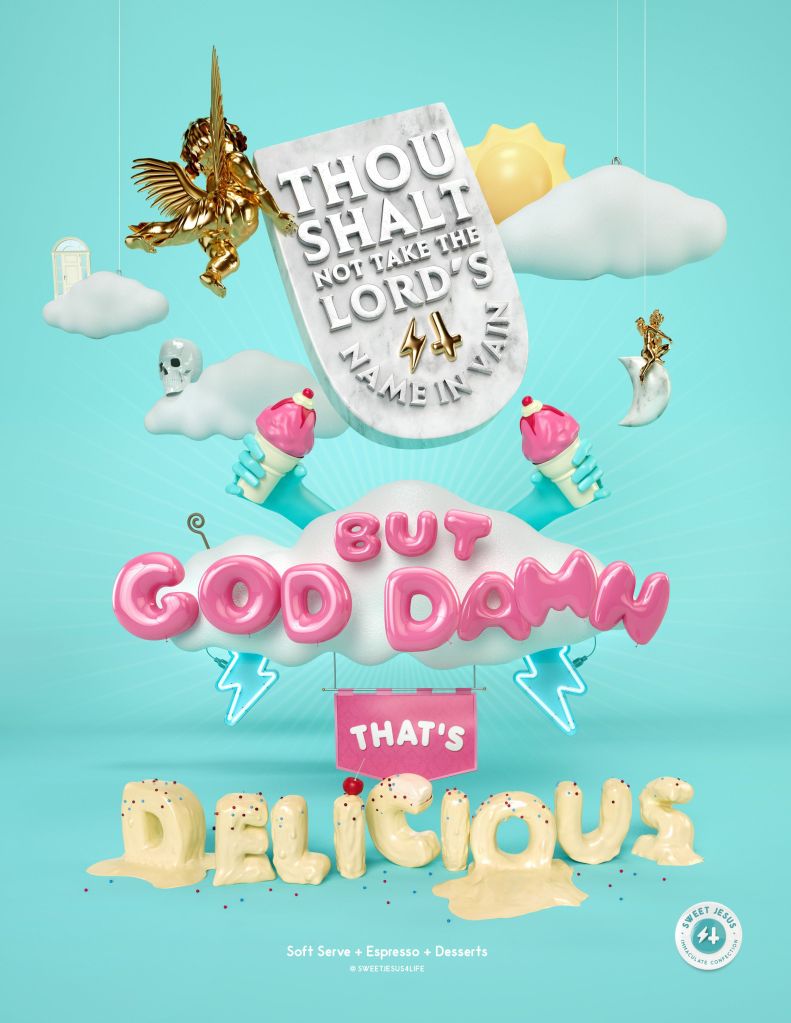

Another example of the celestial interpretation from Renaissance art is the marketing campaigns from an ice-cream company called ‘Sweet Jesus’ by ‘One Method’ agency. The colours of a celestial sky indicate the rising of the sun as a visual representation of the rising of Christ. Unlike Equinox, the Sweet Jesus advert uses a palette of unblended colours with no subtlety to visual references or text. The use of 3D art in the advert establishes a new era from the Renaissance influences it uses, it embraces modern mediums and simple composition yet retains the essence of Christian art. To get their point across they used a biblical commandment and iconography from 16th Century art – not other depictions of divinity, indicating that the divinity in Renaissance is widely understood and encapsulated as though the time itself was ethereal and divine.

Sweet Jesus received backlash of over 10,000 petitions to change their name and campaigns (Independent, 2018), however the brand still appealed to wide audiences through their aesthetic. A third criteria is celestial art as a visual metaphor for the heavens.

IV. Luminance and Colour

The Assumption of the Virgin (1650) by Guercino shows an example of luminance and colour when depicting the Virgin Mary, also present in Sassoferrato’s Virgin Mary (1640). The blue traditionally used in Renaissance art is ultramarine, which because of its rarity exceeded the price of gold. Because of this, artists used it sparingly only to depict the divine, such as the Virgin Mary and heaven itself. The blue symbolises purity and the red represented Mary’s motherhood, which both stem from natural interpretations of blue being water and pure and red being the blood that is shed in childbirth or shared in pregnancy. The two colours together are seen significantly in biblical art and have resurfaced in depicting Superman since 1938 proving again that religion has always been a powerful trigger for artistic expression. Equinox released alongside their celestial poster, a video campaign using

similar colours and luminance.

The 2020 Equinox by Droga5, encourages the audience to embrace their inner Narcissus based on a Renaissance take of the Greek God. The provocative campaign directed by Italian Floria Sigismondi paid homage to the techniques of the excess use of chiaroscuro in the light that enhances the ethereal centred figures by the extreme darkness around them. The colours of the Virgin Mary are seen in the ultramarine sky and the red robes of an off-centred figure, that pulls our attention due to the composition that embraces a divine triangle. The Renaissance scenes in the advert revealed a 75% increase in customer engagement (AdWeek, 2020).

The video communicated a luxury by using the rich colours and extreme light that represents our prestigious history as mankind based on the prestigious art it mimics. Then cleverly, Equinox invites the audience to take part in this celebration of life, to be self-centred like Narcissus while inferring that this will make them feel divine based on the imagery. The title The Most Selfless Act of All (2020) suggests that self-indulgence and hedonism are a part of our nature and history as the concept depicts themes of narcissism in the art of a traditional museum. As viewers, we are being primed in believing we can be divine while living vicariously through the divine beings. Identifying the Renaissance as a time of the greatest art acknowledges biblical art as the most influential. Whether blasphemous or erotic doesn’t diminish the fact that it is eternally provocative.

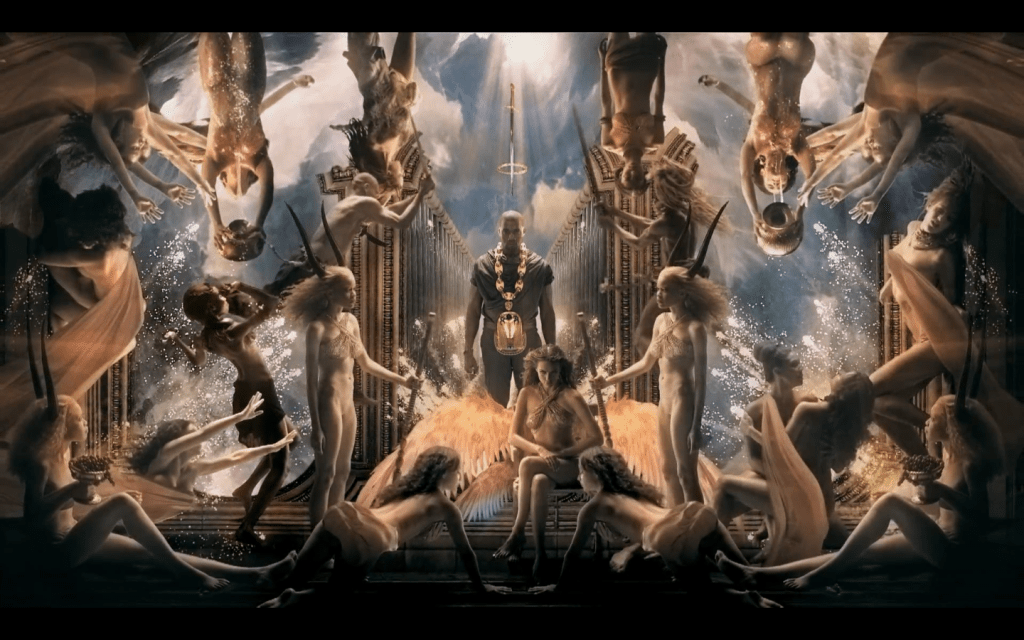

Kanye West, who also goes by a self-proclaimed title ‘Yeezus’, addresses the messianic complex and idolatry in today’s cultural system of celebrities using provocative imagery. The most evident depiction of this is in artwork for West’s 2010 record Power. The supporting artwork can be defined as a video but is most accurately defined by the director, Marco Brambilla, as a moving painting. It invokes cultural references from the Renaissance period and functions as a modern art montage that, due to its references to the Sistine Chapel, marks a revolutionary change in the way we look at music videos as a medium.

The winged woman at the feet of West signifies the phoenix, due to the carriage of golden wings. The lyrics mention a ‘beautiful death’ and the visuals show West will be killed before the scene cuts to black. West says

“goodbye cruel world / I see you in the morning”, indicates an initiation process that is often metaphorically described as a long night followed by a glorious awakening as a new being.

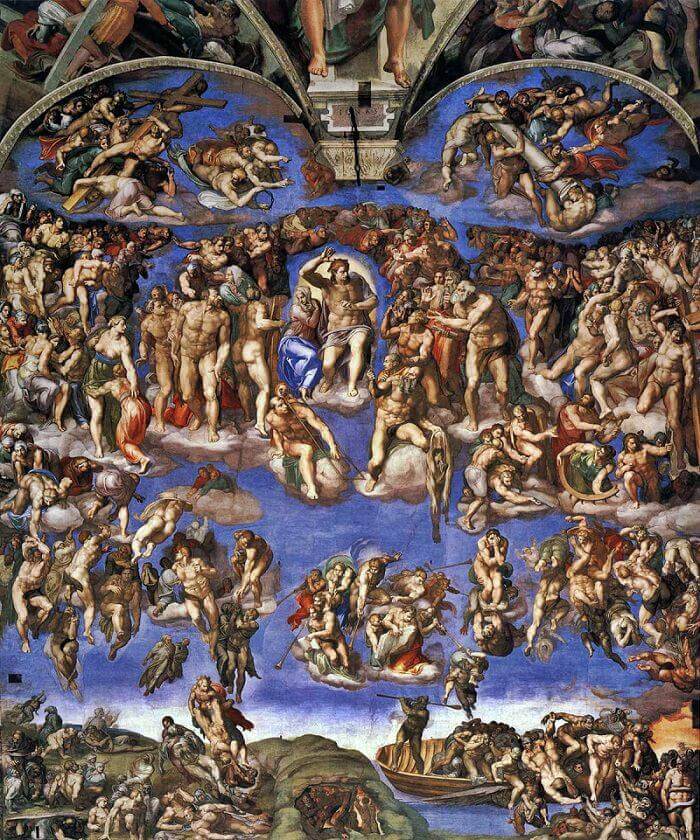

This looming anticipation of death reveals that the complex presence of the phoenix, which myth says rises from the ashes after death, signifies a second coming. Drawing comparisons from Kanye’s rebirth to biblical stories of Christ who was resurrected. The composition of the art by Brambilla is comparable to Michelangelo’s painting The Last Judgement (1541) which would highlight the scrutiny West feels for being idolised.

A reference to Dante Aligheri’s Paradiso (1308) in the top part of the painting establishes Michelangelo’s acknowledgment with the poet, while he references Dante below suggesting Inferno and act as Michelangelo’s criticism within the hierarchy of the Church.

Similar to Michelangelo’s veiled criticism, the Renaissance references in Power act as a powerful lens to interrogate the social systems of today and a criticism of those in power. This message, that is supported by the Christian iconography could be seen as irreverent and satirical, but for Renaissance art this wouldn’t be the first time. The difference here being that the song is an example of how divinity in Renaissance art can be adorned by the audience through the incantation of lyrics – majorly because of the divine art it is associated with. The tribal chants enhance the hyper-sensationalism of the visuals and present a primitive and apocalyptic feel that entrances the audience.

The 43-second-long story by Brambilla uses visual themes of heavy contrast as homage to chiaroscuro, golden skin and symmetrical symbols to deeper the connection to the traditional depictions of divinity in Renaissance art. Similarly, The Last Judgement by Michelangelo uses the purity of ultramarine, richness of red and the golden skin to illuminate the darker areas as well as proximity and depth. The ability to portray divinity in Renaissance using luminance and colour identifies a fourth and final criteria.

Conclusion

Without going down every rabbit hole that is present in this vast topic of works, such as Egyptian influences or gender biases, the research aims to satisfy the identification of necessary criteria to implement in practice. Historical nostalgia and the antithesis of the tech aesthetic is relevant right now because we’re living in times of extreme unreality, futurism and advanced technology. But popular shows like Good Omens (2019) and Miracle Workers (2019) based on a satirical marriage between religion and technology, proves a new rebirth – a new renaissance, in a digital age. Using the criteria, a project such as iDivine could prove the lucrative and widely appealing reproduction of divinity in Renaissance, a visual representation of chaos of reality.

Read about Christianity in Britain here.

Bibliography

Bernstein, P. (2020). The 3 Rules of Transmedia Storytelling from Transmedia Guru Jeff Gomez. [online] IndieWire. Available at: https://www.indiewire.com/2013/12/the-3-rules-of-transmedia-storytelling-from-transmedia-guru-jeff-gomez-32325/ [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

Harvard Business Review. (2020). Brands Are Behaving Like Organized Religions. [online] Available at:

https://hbr.org/2016/02/brands-are-behaving-like-organized-religions [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

Campbell, J. (1968). The hero with a thousand faces. [New York]: Pantheon Books.

de Campos, D., Malysz, T., Bonatto-Costa, J., Pereira Jotz, G., Pinto de Oliveira Junior, L. and Oxley da Rocha, A. (2015). More than a neuroanatomical representation in The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti, a representation of the Golden Ratio. Clinical Anatomy, 28(6), pp.702-705.

Hahn, D. (2008). The alchemy of animation. New York: Disney Editions.

Meisner, G. and Araujo, R. (2018). The Golden Ratio. Minneapolis: Quayside Publishing Group.

Italianrenaissance.org. (2013). Michelangelo’s Pieta – ItalianRenaissance.org. [online] Available at:

http://www.italianrenaissance.org/michelangelos-pieta/ [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

Abc-people.com. (2020). Pythagoras on the fresco “The School of Athens” by Raphael Sanzio. [online] Available at: http://www.abc-people.com/data/rafael-santi/pythagoras.htm [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

Ramsahoye, R. and Finlay, J. (2010). Pythagorean Theorems and Renaissance Ideals of Friendship in ‘The Ambassadors’. artfractures, (4).

One Method. (2018). Sweet Jesus. [online] Available at: https://onemethod.com/experiments/sweet-jesus [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

The Independent. (2018). Sweet Jesus ice cream chain refuses to change ‘blasphemous’ name. [online] Available at:

https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/sweet-jesus-ice-cream-chain-blasphemous-christian-petition-toronto-canada-a8277186.html [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

The National Gallery, L. (2020). Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696 – 1770) | National Gallery, London. [online] Nationalgallery.org.uk. Available at: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/giovanni-battista-tiepolo [Accessed 28 Jan. 2020].

Vasari, G. (2012). Vasari on Technique. Dover Publications.